[unable to retrieve full-text content]

China Factory Activity Worsens in December as Covid Spreads BloombergChina Factory Activity Worsens in December as Covid Spreads - Bloomberg

Read More

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

China Factory Activity Worsens in December as Covid Spreads Bloomberg[unable to retrieve full-text content]

The Stephanomics Guide to the Global Economy in 2023 BloombergPublished

2 hours agoon

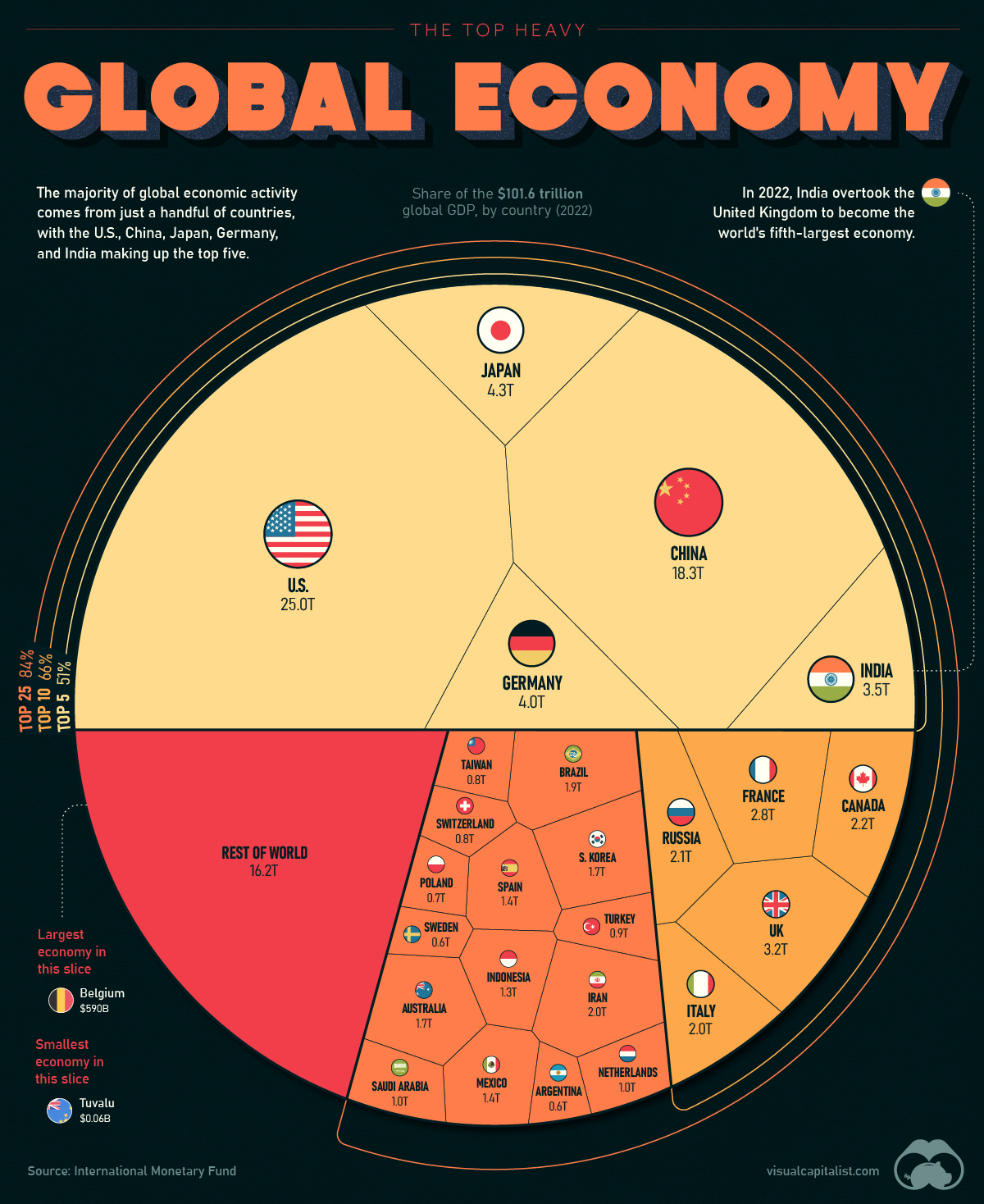

As 2022 comes to a close we can recap many historic milestones of the year, like the Earth’s population hitting 8 billion and the global economy surpassing $100 trillion.

In this chart, we visualize the world’s GDP using data from the IMF, showcasing the biggest economies and the share of global economic activity that they make up.

The global economy can be thought of as a pie, with the size of each slice representing the share of global GDP contributed by each country. Currently, the largest slices of the pie are held by the United States, China, Japan, Germany, and India, which together account for more than half of global GDP.

Here’s a look at every country’s share of the world’s $101.6 trillion economy:

| Rank | Country | GDP (Billions, USD) |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | 🇺🇸 United States | $25,035.2 |

| #2 | 🇨🇳 China | $18,321.2 |

| #3 | 🇯🇵 Japan | $4,300.6 |

| #4 | 🇩🇪 Germany | $4,031.1 |

| #5 | 🇮🇳 India | $3,468.6 |

| #6 | 🇬🇧 United Kingdom | $3,198.5 |

| #7 | 🇫🇷 France | $2,778.1 |

| #8 | 🇨🇦 Canada | $2,200.4 |

| #9 | 🇷🇺 Russia | $2,133.1 |

| #10 | 🇮🇹 Italy | $1,997.0 |

| #11 | 🇮🇷 Iran | $1,973.7 |

| #12 | 🇧🇷 Brazil | $1,894.7 |

| #13 | 🇰🇷 South Korea | $1,734.2 |

| #14 | 🇦🇺 Australia | $1,724.8 |

| #15 | 🇲🇽 Mexico | $1,424.5 |

| #16 | 🇪🇸 Spain | $1,389.9 |

| #17 | 🇮🇩 Indonesia | $1,289.4 |

| #18 | 🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia | $1,010.6 |

| #19 | 🇳🇱 Netherlands | $990.6 |

| #20 | 🇹🇷 Turkey | $853.5 |

| #21 | 🇹🇼 Taiwan | $828.7 |

| #22 | 🇨🇭 Switzerland | $807.4 |

| #23 | 🇵🇱 Poland | $716.3 |

| #24 | 🇦🇷 Argentina | $630.7 |

| #25 | 🇸🇪 Sweden | $603.9 |

| #26 | 🇧🇪 Belgium | $589.5 |

| #27 | 🇹🇭 Thailand | $534.8 |

| #28 | 🇮🇱 Israel | $527.2 |

| #29 | 🇮🇪 Ireland | $519.8 |

| #30 | 🇳🇴 Norway | $504.7 |

| #31 | 🇳🇬 Nigeria | $504.2 |

| #32 | 🇦🇪 United Arab Emirates | $503.9 |

| #33 | 🇪🇬 Egypt | $469.1 |

| #34 | 🇦🇹 Austria | $468.0 |

| #35 | 🇧🇩 Bangladesh | $460.8 |

| #36 | 🇲🇾 Malaysia | $434.1 |

| #37 | 🇸🇬 Singapore | $423.6 |

| #38 | 🇻🇳 Vietnam | $413.8 |

| #39 | 🇿🇦 South Africa | $411.5 |

| #40 | 🇵🇭 Philippines | $401.7 |

| #41 | 🇩🇰 Denmark | $386.7 |

| #42 | 🇵🇰 Pakistan | $376.5 |

| #43 | 🇭🇰 Hong Kong SAR | $368.4 |

| #44 | 🇨🇴 Colombia | $342.9 |

| #45 | 🇨🇱 Chile | $310.9 |

| #46 | 🇷🇴 Romania | $299.9 |

| #47 | 🇨🇿 Czech Republic | $295.6 |

| #48 | 🇮🇶 Iraq | $282.9 |

| #49 | 🇫🇮 Finland | $281.4 |

| #50 | 🇵🇹 Portugal | $255.9 |

| #51 | 🇳🇿 New Zealand | $242.7 |

| #52 | 🇵🇪 Peru | $239.3 |

| #53 | 🇰🇿 Kazakhstan | $224.3 |

| #54 | 🇬🇷 Greece | $222.0 |

| #55 | 🇶🇦 Qatar | $221.4 |

| #56 | 🇩🇿 Algeria | $187.2 |

| #57 | 🇭🇺 Hungary | $184.7 |

| #58 | 🇰🇼 Kuwait | $183.6 |

| #59 | 🇲🇦 Morocco | $142.9 |

| #60 | 🇦🇴 Angola | $124.8 |

| #61 | 🇵🇷 Puerto Rico | $118.7 |

| #62 | 🇪🇨 Ecuador | $115.5 |

| #63 | 🇰🇪 Kenya | $114.9 |

| #64 | 🇸🇰 Slovakia | $112.4 |

| #65 | 🇩🇴 Dominican Republic | $112.4 |

| #66 | 🇪🇹 Ethiopia | $111.2 |

| #67 | 🇴🇲 Oman | $109.0 |

| #68 | 🇬🇹 Guatemala | $91.3 |

| #69 | 🇧🇬 Bulgaria | $85.0 |

| #70 | 🇱🇺 Luxembourg | $82.2 |

| #71 | 🇻🇪 Venezuela | $82.1 |

| #72 | 🇧🇾 Belarus | $79.7 |

| #73 | 🇺🇿 Uzbekistan | $79.1 |

| #74 | 🇹🇿 Tanzania | $76.6 |

| #75 | 🇬🇭 Ghana | $76.0 |

| #76 | 🇹🇲 Turkmenistan | $74.4 |

| #77 | 🇱🇰 Sri Lanka | $73.7 |

| #78 | 🇺🇾 Uruguay | $71.2 |

| #79 | 🇵🇦 Panama | $71.1 |

| #80 | 🇦🇿 Azerbaijan | $70.1 |

| #81 | 🇭🇷 Croatia | $69.4 |

| #82 | 🇨🇮 Côte d'Ivoire | $68.6 |

| #83 | 🇨🇷 Costa Rica | $68.5 |

| #84 | 🇱🇹 Lithuania | $68.0 |

| #85 | 🇨🇩 Democratic Republic of the Congo | $63.9 |

| #86 | 🇷🇸 Serbia | $62.7 |

| #87 | 🇸🇮 Slovenia | $62.2 |

| #88 | 🇲🇲 Myanmar | $59.5 |

| #89 | 🇺🇬 Uganda | $48.4 |

| #90 | 🇯🇴 Jordan | $48.1 |

| #91 | 🇹🇳 Tunisia | $46.3 |

| #92 | 🇨🇲 Cameroon | $44.2 |

| #93 | 🇧🇭 Bahrain | $43.5 |

| #94 | 🇧🇴 Bolivia | $43.4 |

| #95 | 🇸🇩 Sudan | $42.8 |

| #96 | 🇵🇾 Paraguay | $41.9 |

| #97 | 🇱🇾 Libya | $40.8 |

| #98 | 🇱🇻 Latvia | $40.6 |

| #99 | 🇪🇪 Estonia | $39.1 |

| #100 | 🇳🇵 Nepal | $39.0 |

| #101 | 🇿🇼 Zimbabwe | $38.3 |

| #102 | 🇸🇻 El Salvador | $32.0 |

| #103 | 🇵🇬 Papua New Guinea | $31.4 |

| #104 | 🇭🇳 Honduras | $30.6 |

| #105 | 🇹🇹 Trinidad and Tobago | $29.3 |

| #106 | 🇰🇭 Cambodia | $28.3 |

| #107 | 🇮🇸 Iceland | $27.7 |

| #108 | 🇾🇪 Yemen | $27.6 |

| #109 | 🇸🇳 Senegal | $27.5 |

| #110 | 🇿🇲 Zambia | $27.0 |

| #111 | 🇨🇾 Cyprus | $26.7 |

| #112 | 🇬🇪 Georgia | $25.2 |

| #113 | 🇧🇦 Bosnia and Herzegovina | $23.7 |

| #114 | 🇲🇴 Macao SAR | $23.4 |

| #115 | 🇬🇦 Gabon | $22.2 |

| #116 | 🇭🇹 Haiti | $20.2 |

| #117 | 🇬🇳 Guinea | $19.7 |

| #118 | West Bank and Gaza | $18.8 |

| #119 | 🇧🇳 Brunei | $18.5 |

| #120 | 🇲🇱 Mali | $18.4 |

| #121 | 🇧🇫 Burkina Faso | $18.3 |

| #122 | 🇦🇱 Albania | $18.3 |

| #123 | 🇧🇼 Botswana | $18.0 |

| #124 | 🇲🇿 Mozambique | $17.9 |

| #125 | 🇦🇲 Armenia | $17.7 |

| #126 | 🇧🇯 Benin | $17.5 |

| #127 | 🇲🇹 Malta | $17.2 |

| #128 | 🇬🇶 Equatorial Guinea | $16.9 |

| #129 | 🇱🇦 Laos | $16.3 |

| #130 | 🇯🇲 Jamaica | $16.1 |

| #131 | 🇲🇳 Mongolia | $15.7 |

| #132 | 🇳🇮 Nicaragua | $15.7 |

| #133 | 🇲🇬 Madagascar | $15.1 |

| #134 | 🇬🇾 Guyana | $14.8 |

| #135 | 🇳🇪 Niger | $14.6 |

| #136 | 🇨🇬 Republic of Congo | $14.5 |

| #137 | 🇲🇰 North Macedonia | $14.1 |

| #138 | 🇲🇩 Moldova | $14.0 |

| #139 | 🇹🇩 Chad | $12.9 |

| #140 | 🇧🇸 The Bahamas | $12.7 |

| #141 | 🇳🇦 Namibia | $12.5 |

| #142 | 🇷🇼 Rwanda | $12.1 |

| #143 | 🇲🇼 Malawi | $11.6 |

| #144 | 🇲🇺 Mauritius | $11.5 |

| #145 | 🇲🇷 Mauritania | $10.1 |

| #146 | 🇹🇯 Tajikistan | $10.0 |

| #147 | 🇰🇬 Kyrgyzstan | $9.8 |

| #148 | 🇽🇰 Kosovo | $9.2 |

| #149 | 🇸🇴 Somalia | $8.4 |

| #150 | 🇹🇬 Togo | $8.4 |

| #151 | 🇲🇪 Montenegro | $6.1 |

| #152 | 🇲🇻 Maldives | $5.9 |

| #153 | 🇧🇧 Barbados | $5.8 |

| #154 | 🇫🇯 Fiji | $4.9 |

| #155 | 🇸🇸 South Sudan | $4.8 |

| #156 | 🇸🇿 Eswatini | $4.7 |

| #157 | 🇸🇱 Sierra Leone | $4.1 |

| #158 | 🇱🇷 Liberia | $3.9 |

| #159 | 🇩🇯 Djibouti | $3.7 |

| #160 | 🇧🇮 Burundi | $3.7 |

| #161 | 🇦🇼 Aruba | $3.5 |

| #162 | 🇦🇩 Andorra | $3.3 |

| #163 | 🇸🇷 Suriname | $3.0 |

| #164 | 🇧🇹 Bhutan | $2.7 |

| #165 | 🇧🇿 Belize | $2.7 |

| #166 | 🇱🇸 Lesotho | $2.5 |

| #167 | 🇨🇫 Central African Republic | $2.5 |

| #168 | 🇹🇱 Timor-Leste | $2.4 |

| #169 | 🇪🇷 Eritrea | $2.4 |

| #170 | 🇬🇲 The Gambia | $2.1 |

| #171 | 🇨🇻 Cabo Verde | $2.1 |

| #172 | 🇸🇨 Seychelles | $2.0 |

| #173 | 🇱🇨 St. Lucia | $2.0 |

| #174 | 🇦🇬 Antigua and Barbuda | $1.7 |

| #175 | 🇬🇼 Guinea-Bissau | $1.6 |

| #176 | 🇸🇲 San Marino | $1.6 |

| #177 | 🇸🇧 Solomon Islands | $1.6 |

| #178 | 🇰🇲 Comoros | $1.2 |

| #179 | 🇬🇩 Grenada | $1.2 |

| #180 | 🇰🇳 St. Kitts and Nevis | $1.1 |

| #181 | 🇻🇺 Vanuatu | $1.0 |

| #182 | 🇻🇨 St. Vincent and the Grenadines | $1.0 |

| #183 | 🇼🇸 Samoa | $0.83 |

| #184 | 🇩🇲 Dominica | $0.60 |

| #185 | 🇸🇹 São Tomé and Príncipe | $0.51 |

| #186 | 🇹🇴 Tonga | $0.50 |

| #187 | 🇫🇲 Micronesia | $0.43 |

| #188 | 🇲🇭 Marshall Islands | $0.27 |

| #189 | 🇵🇼 Palau | $0.23 |

| #190 | 🇰🇮 Kiribati | $0.21 |

| #191 | 🇳🇷 Nauru | $0.13 |

| #192 | 🇹🇻 Tuvalu | $0.06 |

| Total World GDP | $101,559.3 |

Just five countries make up more than half of the world’s entire GDP in 2022: the U.S., China, Japan, India, and Germany. Interestingly, India replaced the UK this year as a top five economy.

Adding on another five countries (the top 10) makes up 66% of the global economy, and the top 25 countries comprise 84% of global GDP.

The rest of the world — the remaining 167 nations — make up 16% of global GDP. Many of the smallest economies are islands located in Oceania.

Here’s a look at the 20 smallest economies in the world:

| Country | GDP (Billions, USD) |

|---|---|

| 🇹🇻 Tuvalu | $0.06 |

| 🇳🇷 Nauru | $0.13 |

| 🇰🇮 Kiribati | $0.21 |

| 🇵🇼 Palau | $0.23 |

| 🇲🇭 Marshall Islands | $0.27 |

| 🇫🇲 Micronesia | $0.43 |

| 🇹🇴 Tonga | $0.50 |

| 🇸🇹 São Tomé and Príncipe | $0.51 |

| 🇩🇲 Dominica | $0.60 |

| 🇼🇸 Samoa | $0.83 |

| 🇻🇨 St. Vincent and the Grenadines | $0.95 |

| 🇻🇺 Vanuatu | $0.98 |

| 🇰🇳 St. Kitts and Nevis | $1.12 |

| 🇬🇩 Grenada | $1.19 |

| 🇰🇲 Comoros | $1.24 |

| 🇸🇧 Solomon Islands | $1.60 |

| 🇸🇲 San Marino | $1.62 |

| 🇬🇼 Guinea-Bissau | $1.62 |

| 🇦🇬 Antigua and Barbuda | $1.69 |

| 🇱🇨 St. Lucia | $1.97 |

Tuvalu has the smallest GDP of any country at just $64 million. Tuvalu is one of a dozen nations with a GDP of less than one billion dollars.

Heading into 2023, there is much economic uncertainty. Many experts are anticipating a brief recession, although opinions differ on the definition of “brief”.

Some experts believe that China will buck the trend of economic downturn. If this prediction comes true, the country could own an even larger slice of the global GDP pie in the near future.

The global economy had a rocky year in 2022.

As the worst of COVID-19’s effects on public health receded, the war in Ukraine and China’s tough “zero COVID” curbs injected new chaos into global supply chains. Food and energy prices soared as inflation in many economies hit four-decade highs.

After a tumultuous year, the global economy heads into 2023 in choppy waters.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine continues to roil food and energy markets, while rising interest rates threaten to smother the still-fragile post-pandemic recovery.

On the positive side of the ledger, China’s reopening after three years of strict pandemic curbs offers a confidence boost for the global recovery — albeit tempered by fears that the rampant spread of the virus among the country’s 1.4 billion people could give rise to more lethal variants.

Inflation is expected to decline globally in 2023 but nonetheless remain painfully high.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has predicted global inflation will hit 6.5 percent next year, down from 8.8 percent in 2022. Developing economies are expected to have less relief, with inflation projected to only ease to 8.1 percent in 2023.

“It’s likely that inflation will remain stubbornly higher than the 2 percent that most Western central banks have set as their benchmark,” Alexander Tziamalis, a senior economics lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University, told Al Jazeera.

“Energy and raw materials will remain expensive for some time. The partial reversal of globalisation means more expensive imports, shortages of labour in many Western countries leads to more expensive production, and green transition measures to combat the greatest threat our species faces are all leading to higher inflation than we’ve been used to through the 2010s.”

While price growth is expected to ease in 2023, economic growth is certain to slow sharply alongside rising interest rates, too.

The IMF has estimated that the global economy will grow just 2.7 percent in 2023, down from 3.2 percent in 2022. The OECD has projected a less lofty performance this year of 2.2 percent growth, compared with 3.1 percent in 2022.

Many economists are more pessimistic and believe a global recession is likely in 2023, barely three years after the downturn caused by the pandemic.

In a column last month, Zanny Minton Beddoes, editor-in-chief of The Economist, painted a grim picture that was summed up by the article’s unequivocal title: “Why a global recession is inevitable in 2023”.

Even if the global economy does not technically fall into recession — broadly defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth — the IMF’s chief economist recently warned that 2023 may still feel like one for many people due to the combination of slowing growth, high prices and rising interest rates.

“The three largest economies, the US, China and the euro area, will continue to stall,” Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas said in October. “In short, the worst is yet to come, and for many people, 2023 will feel like a recession.”

After nearly three years of punishing lockdowns, mass testing and border closures, China earlier this month began the process of unwinding its controversial “zero COVID” policy after rare mass protests.

With draconian restrictions inside the country a thing of the past, China’s international borders are set to reopen from January 8.

The reopening of the world’s second-largest economy — which has slowed dramatically during the last year — should inject new momentum into the global recovery.

A rebound in Chinese consumer demand would give a boost to major exporters such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore, while the end of restrictions offers relief to global brands from Apple to Tesla that suffered repeated disruptions under “zero COVID”.

At the same time, China’s rapid U-turn away from “zero COVID” carries significant risks.

While Beijing has stopped publishing COVID statistics, hospitals across China have been flooded with the sick, while morgues and crematoriums have reported being overwhelmed with the influx of bodies.

Some medical experts have estimated that China could see up to 2 million deaths in the coming months.

With the virus spreading rapidly among China’s colossal population, some health experts have also expressed concerns about the emergence of new and more dangerous variants.

“Barring this very disruptive opening up, I think that the market will do great,” Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, told Al Jazeera.

“I would say once people see the end of the tunnel, so maybe the end of January, the end of the Chinese New Year, I would argue that’s when markets are really going to read a rapid recovery of the Chinese economy,” Garcia-Herrero added.

“The other thing to watch is if there’s a major mutation, and mutations can be either less lethal but they could also be more lethal, and I think if the latter happens, and we start seeing closures of borders again, that would be traumatic for investor confidence.”

Despite the economic devastation wrought by COVID-19 and lockdowns, bankruptcies in fact declined in many countries in 2020 and 2021 due to a combination of out-of-court arrangements with creditors and large government stimulus.

In the United States, for example, 16,140 businesses filed for bankruptcy in 2021, and 22,391 businesses did so in 2020, compared with 22,910 in 2019.

That trend is expected to reverse in 2023 amid rising energy prices and interest rates.

Allianz Trade has estimated that bankruptcies globally will rise more than 10 percent in 2022 and 19 percent in 2023, eclipsing pre-pandemic levels.

“The COVID pandemic forced many businesses to take on substantial loans, worsening a situation of increasing dependence on cheap loans to make up for the loss of Western competitiveness due to globalisation,” Tziamalis said.

“The survival of highly indebted businesses is now called into question as they face a perfect storm of higher interest rates, higher energy prices, more expensive raw materials and less consumption spending by consumers … It is also worth pointing out that the appetite of Western governments for any direct help to the private sector has been curbed by their increased deficits and prioritisation of support for households.”

Efforts to roll back globalisation accelerated this year and look set to continue apace in 2023.

Since its launch under the Trump administration, the US-China trade and tech war has deepened under US President Joe Biden.

In August, Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act blocking the export of advanced chips and manufacturing equipment to China — a move aimed at stifling the development of the Chinese semiconductor industry and bolstering self-sufficiency in chip making.

The passage of the law was just the latest example of a growing trend away from free trade and economic liberalisation towards protectionism and greater self-sufficiency, especially in critical industries linked to national security.

In a speech earlier this month, Morris Chang, the founder of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s biggest chip manufacturer, lamented that globalisation and free trade are “almost dead”.

“The West, and particularly the US, are increasingly threatened by China’s economic trajectory and respond with economic and military pressure against the emerging superpower,” Tziamalis said.

“An outright war over Taiwan is highly unlikely but more expensive imports and slower growth for all countries involved in this trade war are a near certainty.”

(Bloomberg) -- Stocks in Asia fell Thursday as fresh concerns about the spread of Covid-19 from China unnerved investors, dragging US shares lower for a second day.

Australian and Japanese shares fell by about 1% and contracts for equity benchmarks in Singapore and Taiwan dropped. The S&P 500 slid 1.2% in thin trading to the lowest level in more than a month.

Australian and New Zealand 10-year government bond yields climbed. The 10-year Treasury yield and the dollar were steady after rising Wednesday.

Appetite for risk waned on news that the US would require inbound airline passengers from China to show a negative Covid-19 test prior to entry. In Italy, health officials said they would test arrivals from China and said almost half of passengers on two flights from China to Milan were found to have the virus.

The prospect of further pandemic disruption to fragile supply chains as central banks grapple to bring inflation under control damped sentiment in the final trading week of 2022 after a brutal year for financial markets. Global equities have lost a fifth of value, the largest decline since 2008 on an annual basis, and an index of global bonds has slumped 16%. The dollar has surged 7% and the US 10-year yield has jumped to above 3.80% from just 1.5% at the end of 2021.

Hong Kong removed limits on gatherings and testing for travelers in a further unwinding of its last major Covid rules, offering a boost to the global economy but sparking concerns it would amplify inflation pressures and prompt US policy makers to maintain tight monetary settings.

China’s reopening “complicates the Fed’s job with respect to putting a little bit of a bid under oil prices, putting a little bit of a bid under inflation globally, to aggregate demand. That’s going to be one of the biggest things that we’ll be watching in the first half,” said Sameer Samana, senior global market strategist for Wells Fargo Investment Institute, on Bloomberg TV.

Data released Wednesday showed the Federal Reserve’s aggressive tightening policy has taken a toll on the housing market. US pending home sales fell for a sixth consecutive month in November to the second-lowest on record. Borrowing costs have roughly doubled since the start of the year and home sales have been declining for months.

Elsewhere in markets, oil dipped amid thin liquidity as investors weighed the fallout from a Russian ban on exports to buyers that adhere to a price cap.

“We expect the economy to slow materially or enter recession at some point in 2023,” wrote Nancy Tengler, CEO and chief investment officer at Laffer Tengler Investments.

“A severe recession would be bearish for stocks, yet given the resilience of the US economy and the tight labor market, we are expecting a slowdown or shallow and brief recession. That could allow stocks to rally in the second half of 2023,” she said.

Key events this week:

Some of the main moves in markets:

Stocks

Currencies

Cryptocurrencies

Bonds

Commodities

This story was produced with the assistance of Bloomberg Automation.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LOJPVXHDN5NE3JYBZVTZ3MVOHM.JPG)

U.S. and Canadian main indexes closed lower on Wednesday, as investors grappled with mixed economic data, rising COVID cases in China, and geopolitical tensions heading into 2023.

“There was no Santa rally this year. The Grinch showed up this December for investors,” said Greg Bassuk, chief executive at AXS Investments in Port Chester, New York.

December is typically a strong month for equities, with a rally in the week between Christmas and New Year’s. The S&P 500 index has posted only 18 Decembers with losses since 1950, Truist Advisory Services data show.

“Normally a Santa Claus Rally is sparked by hopes of factors that will drive economic and market growth,” Bassuk said. “The negative and mixed economic data, greater concerns around COVID reemergence and ongoing geopolitical tensions and ... all of that also translating Fed policy is all impeding Santa (from) showing up at the end of this year.”

All 11 of the S&P 500 sector indexes fell on Wednesday, with energy stocks as the biggest loser.

Investors have been assessing China’s move to reopen its COVID-battered economy against the backdrop of a surge in infections.

“With this current combination of rising cases with an opening up of China restrictions, we’re seeing that investors are concerned that the ramifications are going to spread through many different industries and sectors as it did in the earlier COVID period,” Bassuk said.

The benchmark S&P 500 is down 20% year-to-date, on track for its biggest annual loss since the financial crisis of 2008. The rout has been more severe for the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite, which closed at the lowest level since July 2020.

While recent data pointing to an easing in inflationary pressures has bolstered hopes of smaller interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, a tight labor market and resilient American economy have spurred worries that rates could stay higher for longer.

Markets are now pricing in 69% odds of a 25-basis point rate hike at the U.S. central bank’s February meeting and see rates peaking at 4.94% in the first half of next year..

Shares of Tesla Inc rose in choppy trade, after hitting its lowest level in more than two years a day earlier. The stock is down nearly 69% for the year.

Southwest Airlines Co dropped a day after the carrier came under fire from the U.S. government for canceling thousands of flights.

According to preliminary data, the S&P 500 lost 46.20 points, or 1.21%, to end at 3,783.05 points, while the Nasdaq Composite lost 138.33 points, or 1.34%, to 10,214.89. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 367.60 points, or 1.11%, to 32,873.96.

The TSX Composite Index was down 222.55 points, or 1.14%, at 19,284.10.

Reuters, Globe staff

Be smart with your money. Get the latest investing insights delivered right to your inbox three times a week, with the Globe Investor newsletter. Sign up today.

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

China Stocks Rally in Hong Kong With Border Reopening, Covid Zero Ending Bloomberg:quality(100):focal(5950x3626:5960x3636)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/Q3Z26MNATVE4TI3K6EQ74SVXG4.jpg)

If the economies of 2020 and 2021 were dominated by the covid shutdowns and the subsequent opening up, 2022 was a year of shocks and aftershocks.

The economy is still clearly one reckoning with covid-19 — a smaller portion of the population is in the labor force, and the in-person economy still has not recovered to its pre-covid strength. But 2022 brought its own unique challenges too, namely a Federal Reserve responding to inflation with the steepest interest rate hikes in decades and a European war between major exporters.

The economy started this year hot, hot, hot. Employers were snapping up labor, and their wages were rising accordingly. Home builders were throwing up everything they could while home sellers were seeing price growth they couldn’t believe — and home buyers took advantage of the last few months of low interest rates to snap up more and more housing across the country.

The Federal Reserve did what it could to put an end to all that. It started raising interest rates in the spring, and the housing market felt the brunt of it. Home sales plummeted, builders stopped building, and stock prices continued a fall that started late last year.

ADVERTISEMENT

But the shocks to the economy weren’t just internal.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the entire global commodities market went haywire. Russia and Ukraine are both massive exporters of agricultural commodities like wheat, while Russia itself exports (or exported) a huge amount of oil and natural gas. Gasoline prices shot up, as did global food prices. And while the Fed had firmly shifted into inflation fighting mode by the summer, its policies take time to have an effect on the economy. All this added up to the biggest annual increase in prices since the early 1980s, with inflation getting just over 9 percent during the summer.

While inflation is still high, it has dramatically come down at the end of the year, with monthly readings showing little increases in prices, thanks largely to the price of gas and goods coming down, even as wage growth remains historically hot.

That’s because all the while, the job market chugged along, even as the economy technically contracted, according to the gross domestic product figures. While job growth now is a fraction of what it was earlier this year, the monthly numbers in the last quarter of the year would have been the envy of any time between 2010 and 2020.

So where does this leave the economy in 2023? Many analysts and economists have long predicted a recession sometime next year, but as of now, the economy is continuing to chug along. One reason many forecasters are pessimistic is because substantial lowering of inflation typically brings along a recession as Federal Reserve interest rate hikes put a chill on the economy.

ADVERTISEMENT

So, the biggest question for 2023, as it has been most of this year, is inflation. Will it continue to fall, and if it doesn’t, what will the Federal Reserve be willing to do — and willing to risk — to make it happen?

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.

(Bloomberg) -- China’s 2021 gross domestic product was about $80 billion larger than first calculated, the National Bureau of Statistics said, a revision that added the equivalent of Ghana’s output to the size of the world’s second-largest economy.

The nation’s GDP was 114.9 trillion yuan ($16.5 trillion), 556.7 billion yuan larger than what was calculated previously, the NBS said in a statement Tuesday. The revision put China’s economic growth last year at 8.4%, compared with 8.1% in the preliminary reading released in January.

The NBS usually releases preliminary GDP results for the previous year in January and final results by the end of the next January, based on revisions for factors such as the collection of more comprehensive data from businesses. Tuesday’s announcement means the comparison base for economic expansion this year has become higher.

China’s economy this year has been battered by repeated Covid outbreaks and an ongoing property downturn. It’s facing more disruptions in the coming months after the government abruptly abandoned the Covid Zero strategy just as cases surged in winter. Economists have forecast the country’s growth to slow to 3% in 2022, before rebounding to 4.9% next year.

Manufacturing and leasing and business services were the main contributors to the changes in 2021 GDP. Their respective value-added output increased by 278.4 billion yuan and 213.4 billion yuan, according to a breakdown provided by the NBS. The value-added output of the construction industry was slashed by 139.7 billion yuan, the biggest reduction among all sectors.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

A few weeks ago, I was buying an iced coffee near my home in San Francisco. I went to pay with cash, and the barista asked me to pay with Apple Pay or a card—she could give me back bills, but did not have any coins.

I would not have thought anything of it, save for the fact that I’ve had similar experiences over and over again of late. My younger son drinks infant formula; I haven’t been able to buy our preferred brand more than once or twice in his lifetime. My older son recently needed an antibiotic for an ear infection; the pediatrician warned my husband he might not be able to find it. My dogs’ veterinarian told me this fall that we should find a new vet; he’s so overbooked that he’s dropping clients. My family is relocating, so we are now scrambling to find nursery-school spots for our kids. As for reasonably priced movers—I’m not sure they exist. I’m probably going to drive the truck myself.

Since the pandemic hit, the economy has been plagued by shortages, some caused or worsened by COVID and many not. Indeed, none of the supply crunches I just cited—coins, formula, antibiotics, veterinary services, early-childhood education, truck drivers—has much to do with the virus still afflicting the world. Something deeper is going on. After the Great Recession, we went through a decade in which economic life was defined by a lack of demand. Now, after the COVID recession, we’ve entered a period in which economic life is defined by a lack of supply.

During the aughts and 2010s, the primary problem was that most families did not earn enough money. Unemployment and underemployment were rampant. Wage growth was slack because companies had no incentive to compete for workers. The middle class was shrinking. And inequality yawned, with the haves getting richer while the have-nots struggled.

This era—which lasted from 2007 until 2018, give or take—was one of extremely loose monetary policy and stingy fiscal policy. The Federal Reserve made it as cheap as it possibly could for businesses and individuals to borrow, but only corporations and the wealthy had the cash on hand to take advantage; Congress, for its part, declined to do much long-term investment and kept its spending stable. It was also an era of low GDP growth, low inflation, and a steady debt-to-GDP ratio, outside of the Great Recession itself. In this environment—let’s call it Demand World—the fundamental problem was the economy’s low appetite for goods and services.

Today, we live in Supply World. People’s primary economic fixation is getting their hands on enough of the stuff they want to buy. Families, for once, have plenty of money. By the middle of the Trump administration, the unemployment rate had fallen low enough and stayed low for long enough that wages started increasing. Businesses began bidding against one another to win over workers. (A Panda Express near my home had a sign up offering $86,000 a year plus a bonus for managers and $19 an hour for its lowest-paying kitchen jobs.) Then the government showered families with money during the pandemic, in the form of stimulus checks, child allowances, small-business relief, and extended unemployment-insurance payments. As a result, inequality has—in a remarkable and underappreciated trend—declined, a lot and fast.

This era—which began in 2018—is one of massive government spending. Congress approved $5 trillion in COVID-related stimulus while the Fed once again dropped borrowing costs to zero during the early pandemic, before hiking rates to tamp down on the torrid pace of cost increases. It is an era of good GDP growth, high inflation, and a ballooning debt-to-GDP ratio.

The issue in Supply World is that shortages, accompanied by rising costs, are keeping businesses and families from getting the things they want and need. We have a labor shortage, caused by COVID-related retirements, COVID-related disability and death, changes in immigration, and low-wage industries struggling to retain workers. The number of people coming into the United States has plummeted, thanks in no small part to the Trump administration’s restrictive border policies and anti-immigrant rhetoric: Immigration added more than a million people to the population in 2016, and a quarter of that many in 2021. At the same time, COVID pushed millions of older Americans to retire, though some are coming back to the labor force now; the virus also killed thousands of workers and maimed millions more. And many industries have struggled to attract workers, due to burnout, dangerous labor conditions, persistently low wages, or some combination of the three.

Then there is the housing shortage, a long-simmering, GDP-stifling national catastrophe, one responsible for problems as varied as the homelessness crisis, falling fertility rates, low productivity growth, and the lack of cool new music. For decades, places like New York and the Bay Area have created more new jobs than they have permitted new homes, leading to escalating prices and long commutes. Those superstar cities have exported their shortages around the country in recent years.

Finally, we face persistent shortages of consumer goods and services: life-saving CPAP units, children’s cough medicines, mid-range couches. Service shortages are in some cases a direct result of the housing shortage and the labor shortage: Getting affordable child care in cities such as Seattle and New York is impossible because they are so expensive for child-care workers to live in, and because there aren’t enough workers in the country to begin with, thanks in part to President Donald Trump. As for the ongoing shortages of stuff, they are due to COVID-related supply-chain disruptions, the sudden surge in consumer spending, and a lack of corporate investment in the Demand World era.

Indeed, Demand World in no small part created Supply World: The entire economy tilted toward producing goods and services for the tiny elite, rather than the middle class. And the lack of demand made it hard to see the lack of supply as a problem. Homelessness got cast as a poverty problem, not a housing-stock problem. The decline of domestic manufacturing got cast as a crisis for the Rust Belt, not for everyone who might want to feed their preemie or bike to work.

With the economy slowing and interest rates going up, might we end up back in Demand World? I asked that question of the former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, who in 2013 began warning that the global economy was entering a period of “secular stagnation,” characterized by low investment, low productivity growth, and low interest rates. To boost growth, he argued, the government might have to run deficits indefinitely.

“I don’t think anybody can know whether we’re headed back to secular stagnation or not,” he told me. On one hand, he said, the country’s workforce had gotten older. The pace of technological change seemed to have slowed. The cost of capital goods had fallen, and corporate profit shares had grown. On the other hand, he noted, the country was running large deficits. Labor unions had gotten more active, and the government more progressive. He also said that he imagined the clean-energy transformation might provide a burst of growth.

So might investment in child care, housing, and domestic manufacturing. So might letting in millions more immigrants. So might deploying the astonishing new technologies emerging from Silicon Valley. Strong demand and ample supply—that’s the world we all should want.

Israel is the fourth-best-performing economy in 2022 among a list of OECD countries, according to a ranking compiled by The Economist.

The British weekly cited Israel’s well-performing economy as one of the “pleasant surprises” in 2022 “despite political chaos” wrought by the government’s collapse, which took Israelis to the polls for a fifth time in less than four years.

The Economist’s ranking is based on an overall score measured by five economic and financial indicators: gross domestic debt (GDP), inflation, inflation breadth, stock market performance and government debt.

Israel’s economy shared the fourth place with Spain and was ranked after Ireland among the 34 wealthy OECD countries cited in the survey. Greece scored the top spot followed by Portugal in second place, while Latvia and Estonia came at the bottom of the list. Japan, France, and Italy made it into the top 10. Meanwhile, the US economy, which grew at a rate of 0.2%, ranked 20th, and Germany, “despite poitical stability,” is in 30th place, according to the Economist.

Countries, including Spain and Israel, that are not dependent on oil and gas delivery from Russia fared better than average, the survey found.

Sign up for the Tech Israel Daily and never miss Israel's top tech stories

“Those reliant on Vladimir Putin for fuel have truly suffered,” the Economist noted. “In Latvia average consumer prices have risen by a fifth.”

The port in Haifa with anchor ships, cranes and cargo containers. (MagioreStock via iStock by Getty Images)

Israel’s economy is projected to have grown at a rate of 6.3% in 2022, according to Finance Ministry estimates, following its even faster expansion of 8.1% in 2021, the year of recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. That compares with projected GDP growth of 3% among world economies for this year, according to an OECD outlook.

Israeli exports, which comprise about 30% of the country’s economic activity, are expected to have increased by more than 10% to record highs of between $160 billion and $165 billion in 2022, according to a conservative estimate published on Sunday by the Economy Ministry’s Foreign Trade Administration (FTA).

The exports of services, including Israeli technology services such as software and various research and development (R&D) solutions, likely exceeded exports of goods for the second consecutive year, with 51% for services and 49% for goods. Programming and R&D services continue to lead the list of the most exported services, with 42% and 14%, respectively, the FTA stated in the report.

Europe is Israel’s largest trading partner, accounting for 38% of exports, followed by the Americas at 35% and Asia at 24%.

Inflation in Israel for the last 12 months has climbed above the upper limit of the target range of 1% to 3% and stands at 5.3%, though it is significantly lower than in most developed countries.

Looking ahead to 2023, the Finance Ministry earlier this month cut its growth outlook for the country’s economy from 3.5% to 3%, citing a contraction in consumer spending and a slowdown in the global economy, which is expected to grow at a rate of about 2.2%.

(Bloomberg) -- China’s economy continued to slow in December as the massive Covid-19 outbreak spread across the country, with activity slumping as more people stay home to try and avoid getting sick or to recover.

Bloomberg’s aggregate index of eight early indicators showed a contraction in activity in December from an already weak pace in November and the outlook is grim for the new year.

Although there’s no reliable data on the extent of the spread of the virus or the number of sick and dead now, it had reached every province before the end of extensive and regular testing. The canceling of almost all domestic restrictions now means the virus can circulate freely.

Even before the curbs were lifted, China’s economy was struggling, with a slump in consumer spending deepening and industrial output growing the slowest since the spring lockdowns.

The situation was even worse for shops and restaurants in Beijing than it was across the nation as a whole, with retail sales in the city dropping almost 18% in November as both cases and restrictions in the capital increased.

However even though people are now free to move around there’s been little rebound in movement so far this month, according to high-frequency data on subway and road usage.

The 3.6 million trips made on the Beijing subway last Thursday were 70% below the level on the same day in 2019, and traffic congestion on the city’s streets was only 30% of the level in January 2021, according to BloombergNEF. Other major cities such as Chongqing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Tianjin and Wuhan are seeing a similar drop.

That looks to be impacting home and car sales, which both fell in the first weeks of this month. Car sales had been supported by government subsidies and were a bright spot for consumer spending this year, but began dropping last month as consumers pulled back. That in turn hit industrial output, with production of cars dropping for the first time since May, when many factories were forced to close.

However unlike in the spring when it was the Covid Zero policy which caused a shortage of car parts and shuttered some plants, now it is the virus itself which is impacting production, with companies having to deal with more workers getting sick.

The spread of the virus across China has undermined the initial euphoria seen in the stock and commodity markets at the reopening. The Shanghai Composite Index has fallen back near the level it was at just before authorities started relaxing curbs on Nov. 11 and has dropped for the past two weeks.

The price of iron ore was also headed for a modest weekly drop as a surge in Covid cases clouded the near-term demand outlook and undermined the effect of recent announcements of support for the real-estate sector. Chinese steel mills are currently reducing production, Guangfa Futures said in a note, with data from an industry association showing output falling and stockpiles rising in the middle of this month.

The drop in markets mirrors the poor confidence among small businesses, which was in contractionary territory for a third straight month in December, according to Standard Chartered Plc. Although there was a small improvement from November, the main indexes still showed smaller firms weren’t optimistic about the current situation or the future.

The manufacturing sector saw some improvement, with a rise in new orders, sales and production from November “likely reflecting the positive impact of the relaxation of Covid control,” the firm’s economists Hunter Chan and Ding Shuang wrote in the report.

However, “services SMEs continued to face headwinds from weak consumer sentiment amid rising Covid cases,” they wrote in a report last week.

There’s little good news for Chinese firms overseas, with the drop in global trade extending into December, according to early Korean data. That means that China’s exports may fall for a third straight month.

The almost 27% drop in Korean exports to China in the first 20 days of this month shows the weakness of Chinese demand for semiconductors, which has been falling due to a slump in domestic and overseas demand for smartphones and other devices.

Early Indicators

Bloomberg Economics generates the overall activity reading by aggregating a three-month weighted average of the monthly changes of eight indicators, which are based on business surveys or market prices.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Colombia Central Bank Chief Says Interest Rate Hikes Near an End Bloomberg

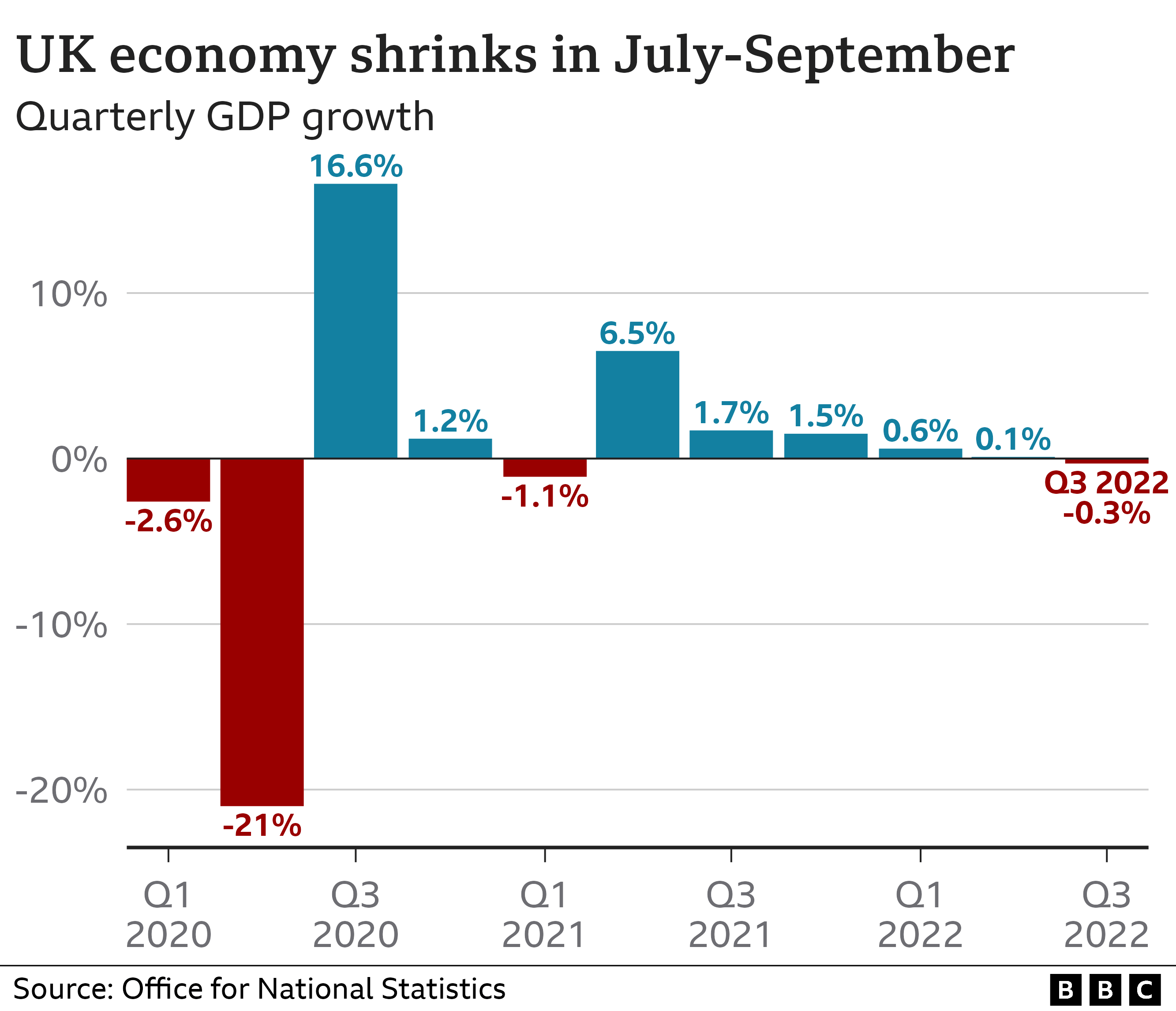

The UK economy shrank by more than first thought in the three months to September, revised figures show.

The economy contracted by 0.3%, compared with a previous estimate of 0.2%, as business investment performed worse than first thought, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

Growth figures for the first half of 2022 have also been revised down.

The UK is forecast to fall into recession in the final three months of the year as soaring prices hit growth.

A country is considered to be in recession when its economy shrinks for two three-month periods - or quarters - in a row. Typically companies make less money, pay falls and unemployment rises, leaving the government with less money in tax to use on public services.

Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said: "Our revised figures show the economy performed slightly less well over the last year than we previously estimated", with manufacturing "notably weaker".

He added that household incomes, when accounting for rising prices, continued to fall, and household spending "fell for the first time since the final Covid-19 lockdown in the spring of 2021".

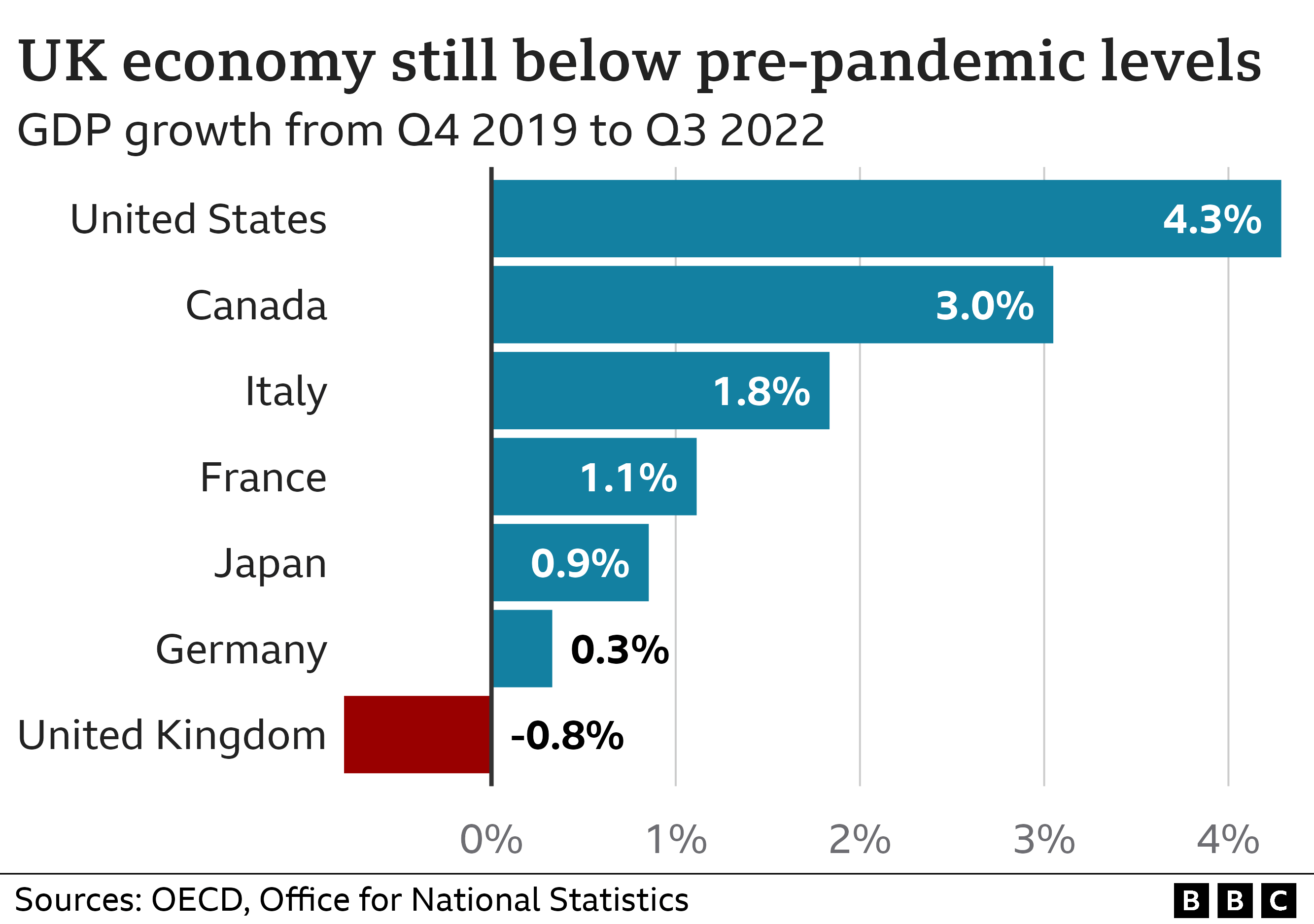

The ONS said that gross domestic product (GDP) - the measure of the size of the economy - was now estimated to be 0.8% below where it was before the pandemic struck, downwardly revised from the previous estimate of 0.4% below.

The economy has been hit as surging energy and food prices push inflation - the rate at which prices rise - to its highest level in 40 years.

It means that consumers are spending less and businesses are cutting investment.

Along with its revision for the July-to-September period, the ONS said the economy also grew less than first estimated in the first half of the year - expanding by 0.6% in the first quarter and 0.1% in the second quarter.

The ONS has previously said growth stood at 0.7% and 0.2% in those quarters respectively.

It is not unusual for the ONS to revise its growth estimates. It produces a first estimate of GDP about 40 days after the quarter in question, at which point only about 60% of the data is available, so the figure is revised later as more information comes in.

We already knew the UK economy shrank in the third quarter of the year while other economies grew. But now the disparity between the UK and the rest of the world looks starker than previously thought.

An economy that remains 0.8% smaller than its pre-pandemic level is in marked contrast to the eurozone - up 2.2% at the last count - or Canada - up by 3%.

The Paris-based think tank the OECD recently forecast in 2023, the UK economy would continue shrinking by more than the rest of the G7, while other economies returned to growth.

There's now a growing body of evidence that some of that underperformance is due to Brexit.

Last week, figures from the ONS indicated that the economy shrank by 0.3% over the August-to-October period.

The government's independent forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), has warned that the UK will fall into a recession "lasting just over a year".

The OBR has predicted that the economy will shrink by 1.4% in 2023 before growth gradually picks up again.

As a result it expects the unemployment rate to rise and house prices to fall sharply as the Bank of England puts up interest rates to control soaring prices.

Last week, the Bank raised its key rate to 3.5%, the highest level for 14 years, which is pushing up repayment costs for people with mortgages and loans.

The UK is not the only country seeing its economy slow down, with the US and eurozone also expected to fall into recession next year.

However, Gabriella Dickens from Pantheon Macroeconomics said she expected the UK to "suffer the deepest recession among major advanced economies in 2023".

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt blamed Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine for the economic difficulties.

"High inflation driven by Putin's invasion of Ukraine is slowing economic growth across the world. No country is immune, least of all Britain," he said.

But responding to the latest ONS figures, Labour's shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves accused the government of losing control over the economy.

"GDP data has been revised down, leaving the UK with the worst growth in the G7 in the last quarter," she tweeted.

"The Tories have lost control of the economy and are leaving millions of working people paying the price."

[unable to retrieve full-text content] The US economy is growing - so where are all the jobs? BBC The US economy is growing - so where ...